It’s fall, and that’s the time when we face one of the harder parts of breeding chickens: culling. I can still remember the first time I realized that we would need to learn to butcher our roosters (and some older hens). While we often can rehome young hens, almost all roosters end up as food for our table. I know it’s a topic that many chicken lovers try to avoid or ignore, but I’d like to offer some thoughts on the rightness of seeing chickens all the way through their life cycles since the reality is that backyard chicken keepers will end up with roosters at some time in their careers.

First of all, though many of us keep chickens as pets, which means they are beloved individuals with names, they are animals: as such, they have no self consciousness. For instance, a chicken does not “say goodbye” to another chicken when they are sold away from each other. Chickens don’t fall in love, get married, or even — as do some animals — mate for life. Neither do chickens freak out at harvest time when cage mates are culled. Chickens are not humans: they do not reason as we do, or know their world as we do. Of course they have feelings, which include pain and fear. But the fear is more like startling, or a flight instinct, than a reasoned dread such as you or I would have in the face of mortal danger.

As a breeder of chickens, it gives me a great sense of purpose to raise birds that are the best that they can be. I choose high quality parent birds, and seek to feed and house them very well so that they will be as healthy (and happy) as possible. I place carefully chosen eggs in an incubator, and hover over it as the eggs set. I watch with amazement as chicks hatch — sometimes even intervening to help, though I’ve found that usually there’s a reason why a chick can’t make it out of the egg unaided. Many of our day-old chicks go off to be adored by others. But many also remain here at Storybook Farm.

I nurture my newborn chicks with electrolytes and apple cider vinegar in their water, medicated feeds that I grind in a blender to make sure they can get it into their newborn beaks. I provide warm lights, and clean, large pens. If they get pasty butts, I wash them off lovingly by hand.

As the birds who remain here grow from fledglings to adolescents, I watch them with delight. I love to see them come running at chow time. I love to hear the young cockerels learning to crow, sounding so much like adolescent boys whose voices have just changed. I laugh over the sparring matches of the young cocks, and am amazed to see the feathers change on pullets with each successive molt. Over and over, I wonder daily at the miracles of life, and growth, and beauty, and sweetness that my birds display.

Both cockerels and pullets frolic all summer at Storybook Farm on green grass, with plenty of sunlight, shade, food, clean water, and company. Unlike most large hatcheries, we do not dispatch young males. We purposefully choose breeds that are 1) heritage, 2) dual purpose (so that they are valuable for both meat and eggs), and 3) homozygous (look the same at birth) so that we sell all our chicks as “straight run” — and raise them the same as well. They all live sweet, pleasant lives while at Storybook Farm.

And then, in the fall, comes time for the hard choices of which chicks will feed us, which pullets will go into our laying flock for eggs, and which of the best birds will be bred to produce the next generation. For me, there’s a holy sense of awe when we go to harvest chickens. I’ve watched each animal its whole life, and now I’m bringing it full circle, and taking it to its final purpose. Each bird here has had a good life. Each bird has been loved and appreciated. And each bird will meet a quick, peaceful, painless, and humane end. It is hard, but it is also good, right, and proper.

All animals die. If I do not lovingly end their lives, their lives will still end eventually, and often in the claws of a predator or in disease brought on by old age. I cannot breed chickens and avoid that fact. Better I do it kindly and quickly than that they fall into hands less loving — like those of predators, or cock fighters, or as a by product of a larger chicken mill.

Deep thoughts about life and death come naturally to me because I am a Christian. I believe that God created chickens for a purpose. Actually, He created them for more than one purpose! Chickens give us so much: their eggs, their friendliness, their funny antics, their silly ways, and ultimately, their bodies. We live in a world where death comes to all. My faith teaches me that death is an evil, but a necessary evil, and sets me free to play my part in this circle of life.

So, I don’t have to ignore or avoid this phase of my responsibilities as a breeder. Bringing chickens into this world includes the duty and privilege of seeing them out of it, and I accept that, humbly and gratefully. I’m standing in the image of my Good Shepherd, Who has determined the roles that each of His people shall play, Who provides for, cares for, loves, and nurtures His children, and Who decides when He will bring them — not to an end, for we are not unconscious animals — but to be home with Him forever.

For me, then, butchering chickens is a sober, sacred business. God gave them life, and then gave them to me. As I choose which ones shall live and die, I reflect in my tiny way His awesome authority. I suppose it could make some people proud to wield such power, or help them become callous/indifferent to death. It has the opposite effect on me: I value the lives of both myself and my chickens more, seeing each day as a joyous gift. I also face death better (mine and my chickens’) by seeing it in right relationship to a bigger picture, and I am grateful.

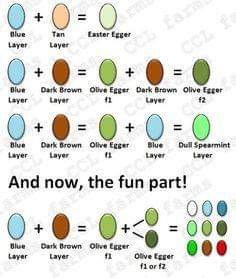

When there is no blue gene present in the pair, any black markings will be normally colored (i.e. they will appear black)

When there is no blue gene present in the pair, any black markings will be normally colored (i.e. they will appear black)

The first hurdle was, as is so often the case, legalities. I consulted the

The first hurdle was, as is so often the case, legalities. I consulted the  )

) )

) It took me a couple of weeks to get all these ducks in a row.

It took me a couple of weeks to get all these ducks in a row.

Chicks and hatching eggs that carry these avian diseases can threaten not only flocks to whom they come, but humans as well. Responsible farmers who sell chicks seek to make sure that the birds they mail are healthy. So, what is the process in becoming certified NPIP and AI clean?

Chicks and hatching eggs that carry these avian diseases can threaten not only flocks to whom they come, but humans as well. Responsible farmers who sell chicks seek to make sure that the birds they mail are healthy. So, what is the process in becoming certified NPIP and AI clean?

Part of the reason is that I’m definitely not the inheritor of my grandmother’s award-winning green thumb. When we got here, the first thing we did was plant an orchard, and that spring, we cleared and terraced and fenced an 1800 square foot garden. For two seasons, we worked with the soil that was there naturally; very little grew. The next two seasons, we built raised beds and used the square foot gardening method. Things came up, but then came the rabbits to eat the tender bean shoots, and the deer finished off the tomatoes just when they were getting ripe after so many days of watering and weeding. That was the last straw for me as a gardener: I’ve been happily buying other people’s veggies ever since. (I do wish that we could grow cilantro, though, in the winter, especially. I use it a lot, and our local grocery store can’t keep it in stock because many people in our small town haven’t yet discovered it and it goes bad. Sigh.)

Part of the reason is that I’m definitely not the inheritor of my grandmother’s award-winning green thumb. When we got here, the first thing we did was plant an orchard, and that spring, we cleared and terraced and fenced an 1800 square foot garden. For two seasons, we worked with the soil that was there naturally; very little grew. The next two seasons, we built raised beds and used the square foot gardening method. Things came up, but then came the rabbits to eat the tender bean shoots, and the deer finished off the tomatoes just when they were getting ripe after so many days of watering and weeding. That was the last straw for me as a gardener: I’ve been happily buying other people’s veggies ever since. (I do wish that we could grow cilantro, though, in the winter, especially. I use it a lot, and our local grocery store can’t keep it in stock because many people in our small town haven’t yet discovered it and it goes bad. Sigh.)

Then, I bought an incubator. And I was so terrified that it would break mid-hatch that I bought a second one just to have as a backup. My first hatching season wasn’t so great. I had 50% hatches, mostly. But the chicks were so cute! (In the picture at the right, you can see my grandson watching a hatching chick long distance via FaceTime.) It has been so much fun to watch the fascination that the children have with both hatching and the cute little chicks. They even like helping with morning and evening feeding and watering when they’re here.

Then, I bought an incubator. And I was so terrified that it would break mid-hatch that I bought a second one just to have as a backup. My first hatching season wasn’t so great. I had 50% hatches, mostly. But the chicks were so cute! (In the picture at the right, you can see my grandson watching a hatching chick long distance via FaceTime.) It has been so much fun to watch the fascination that the children have with both hatching and the cute little chicks. They even like helping with morning and evening feeding and watering when they’re here.